166. DUCK SOUP, 1933

- Jay Jacobson

- Nov 26, 2024

- 20 min read

Updated: Sep 7, 2025

Politics meets pandemonium in this outrageous classic

Comedy and cinema share a glorious bond, as the two virtually grew up together. Starting in the silent days, a handful of comic geniuses emerged whose work was so uniquely funny, they forever changed comedy. Two years after movies began talking, four brothers named the Marx Brothers took movie screens by storm, quickly becoming one of the most influential and important comedy teams in history, and “Duck Soup” is arguably their finest, funniest, and most unbridled cinematic work. Widely considered one of the greatest comedies ever made, the American Film Institute (AFI) named it the 5th Funniest and the 60th Greatest American Film of All-Time, and the BBC named it the 5th Greatest Comedy and the 95th Greatest American Film of All-Time. With so much verbal wit and physical comedy packed into its 68 minutes, it gets deeper and funnier every time I watch it.

“Duck Soup” takes place in the fictional county of Freedonia, where the government has been mismanaged and the country’s desperate for money. It opens as officials ask wealthy widow “Mrs. Teasdale” to bail them out with another $20M. She agrees, but only if the head of the government steps down and “Rufus T. Firefly” is appointed the new leader. The eccentric and incompetent “Firefly” immediately becomes head of Freedonia, and with him comes chaos.

“Firefly’s" unorthodox leadership style and unpredictable antics lead to a series of comical mishaps, including escalating tensions with “Ambassador Trentino” of the neighboring country of Sylvania. “Trentino” is plotting to take over Freedonia, and has employed the help of famous dancer “Vera Marcal” and two spies, “Chicolini” and “Pinky”, to help. “Trentino” and “Firefly” don’t get along, and with the bumbling “Chicolini” and “Pinky”, “Firefly” unintentionally drives Freedonia to war.

Don’t expect realism or a thorough plot. “Duck Soup” is a surreal, anti-fascist political farce that makes fun of everything in its path. Comedy is king and nothing is sacred. The barebones storyline is really just an excuse from which to generate absurd humor, slapstick gags, comical songs, and witty dialogue. After all, it’s a Marx Brothers film, and if you’ve never seen one, buckle your seatbelts because you’re in for a wild ride.

“Duck Soup” stars four Marx Brothers, Groucho (“Firefly”), Harpo (“Pinky”), Chico (“Chicolini”), and Zeppo (“Bob”, “Firefly’s” secretary), each adding their own unique quality to the group’s mix of anarchic humor, clever wordplay, nonsensical antics, playful subversion, and unexpected irreverence, with societal and governmental norms as the target. As the newly appointed "Firefly" cheerfully says in verse to the people of Freedonia: “The last man nearly ruined this place, he didn't know what to do with it. If you think this country's bad off now, just wait til I get through with it”.

In the same verse, "Firefly" sings about his new laws, which include banning chewing gum, whistling, dirty jokes, and pleasure of any kind, laws that destroy the sanctity of marriage, that make sure he gets his share of graft, and a promise that taxes will be raised. But he sets his speech to patriotic songs and delivers it with lighthearted charm, which makes the crowd cheer with unanimous approval. It’s a wildly amusing way to show how easily people can be fooled into supporting a corrupt dictator who doesn’t have their best interests at heart.

The film also pokes fun at bureaucracy (such as when “Firefly” plays a game of Jacks at a government meeting) and the ridiculousness of war (“Firefly’s” uniforms constantly change during battle for no reason (including American Civil War garb, that of a Revolutionary War-era British general, a Boy Scout troop leader, and even a Daniel Boone cap).

But it’s not all political satire. Much of “Duck Soup’s” comedy is simply for the sake of comedy, with hilarious antics that have little or nothing to do with the plot, such as funny business with a sidecar, at a lemonade stand, and most famously, a mirror gag in which “Pinky” pretends to be “Firefly’s” reflection so he doesn’t get caught posing as him. That gag had been done on vaudeville and in some silent movies, but this one is the definitive film version (the most famous is from the TV sitcom “I Love Lucy”, when Harpo reprised it with Lucille Ball in 1955).

Even more prevalent than sight gags and political satire are “Duck Soup’s” nonstop puns and plays on words, to the point that I always discover new ones each time I watch the film. An example is this exchange between “Mrs. Teasdale” and “Firefly” at his welcoming reception:

“Mrs. Teasdale”: “This is a gala day for you.”

“Firefly”: “Well, a gal a day is enough for me. I don’t think I could handle any more.”

Or this between "Firefly" and "Bob" in the middle of war:

"Bob": "Message from the front sir.”

"Firefly": "Oh, I'm sick of messages from the front. Don't we ever get a message from the side? What is it?"

"Bob": "General Smith reports a gas attack. He wants to know what to do.”

"Firefly": "Tell him to take a teaspoon full of bicarbonate of soda and a half a glass of water.”

What’s missing in reading these puns is hearing how the Marx Brothers bring them to life and make absurdity hilarious. Their outrageous, off-the-wall humor, physical and slapstick antics, and intellectual wordplay defied conventional storytelling and reshaped comedy, inspiring legions of subsequent comedians, filmmakers, and writers such as Mel Brooks, Monty Python, Steve Martin, Billy Crystal, Woody Allen, Robin Williams, and countless others. The Marx Brothers were truly one of a kind.

After the loss of their first-born son at seven months old, New York City immigrants Minnie (German) and Sam Marx (French) had five more boys, Chico, Harpo, Groucho, Gummo, and Zeppo. Each were pushed into music by Minnie, who came from a family of performers. With help from her successful vaudevillian brother, the boys began performing (at different times) primarily as singers on vaudeville. One night in a Texas Opera House, someone interrupted their show by shouting that a mule was loose, which prompted audience members to leave to see what was happening. This didn't sit well with fifteen year old Groucho, who began making snide jokes like "The jackass is the finest flower of Tex-ass", which made the audience roar with laughter. That prompted their act to change from singing with some comedy to comedy with some music. All five brothers appeared onstage together briefly in 1915 before Gummo was drafted to serve in World War I. Upon his return, he quit acting and became a successful businessman and talent agent. They were now the Four Marx Brothers, and by the 1920s, their unusual humor (perhaps influenced by the surrealist movement happening at the time), satire, and improvisation made them a giant success. In 1924, they starred in the hit Broadway musical comedy revue "I'll Say She Is”, and then the 1925 smash musical comedy "The Cocoanuts”. In the 2016 documentary “The Marx Brothers: Hollywood’s Kings of Chaos”, Dick Cavett recalled his father fondly telling him about seeing "The Cocoanuts”: “[It was] the only time in [his] life the saying ‘people were falling out of their seats with laughter’ happened. Their legs would go out and they’d slide down and hold themselves”. Another Broadway success followed, "Animal Crackers” in 1928. By this point, Paramount Pictures took notice.

While performing "Animal Crackers” on Broadway nightly, the Marx Brothers shot the film version of "The Cocoanuts" at Paramount's New York City studio by day. Having had performed together for decades onstage, and honing their own comedic character (who they'd play for the rest of their careers), they shared a total ease and familiarity that made their comedy effortless. It translated to the screen and their 1929 film "The Cocoanuts" was an international sensation and one of early sound's most successful movies. Minnie saw the film but died about a month after its release, never seeing the legendary status her sons would achieve. Next came a 1930 movie version of “Animal Crackers”, whose success had the Marx Brothers move to Los Angeles with a three-picture deal from Paramount. Their subsequent movies became more cinematic, starting with 1931’s “Monkey Business”, followed by 1932’s “Horse Feathers” (which earned them the cover of Life magazine). They were now the kings of comedy and the 11th Top Money-Making Stars of 1932 and the 13th of 1933.

Sensing they weren't getting their proper percentage of earnings, after “Horse Feathers” the brothers brought a lawsuit against Paramount, walked out of the studio to go independent, and intended to make a film version of the 1931 hit political satirical play "Of Thee I Sing". They ended up settling with Paramount and "Of Thee I Sing" morphed into "Duck Soup". "Duck Soup" made money, though no one seems to remember how much (Glen Mitchell reports in "Marx Brothers Encyclopedia" that it was the 6th highest-grossing film of 1933, and Variety lists it as the 30th). Since the studio was on the verge of bankruptcy and profits weren't as high as the previous Marx Brothers films, it's thought Paramount considered it a flop.

"Duck Soup" received mixed reviews. Being the height of the Great Depression and the year Adolf Hitler was elected Chancellor of Germany, some felt it was too cynical given what was happening in the world. Italy’s then-dictator, Benito Mussolini took “Duck Soup” as a personal slam, so he banned it in Italy (which thrilled the Marx Brothers). Over time the film became considered their greatest work. After “Duck Soup”, the Marx Brothers and Paramount mutually parted ways, Zeppo stopped performing, and The Four Marx Brothers became The Three Marx Brothers – Groucho, Harpo, and Chico.

After nearly two years off the screen, Chico was playing cards with Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer's (MGM) head of production, Irving Thalberg, who felt the Marx Brothers were not handled properly at Paramount and suggested they sign with MGM, famously telling Chico, "I can produce a Marx Brothers comedy with half the laughs that will do twice the business". The brothers signed, and thus began a change in their movies with stronger storylines, more controlled comedy, no barrage of jokes, a sympathetic Harpo, a clear villain, romantic subplots, and non-comedic musical numbers. The first was 1935's "A Night at the Opera", a major hit and the film that most rivals “Duck Soup” as considered their best film. Thalberg also oversaw their next, 1937's "A Day at the Races”, another big hit, though he tragically died during production. Without their white knight, no one knew how to make their movies successful. They made one at RKO (1938’s "Room Service”) before their final three at MGM, with each progressively worse. After their last, 1941's "The Big Store”, they decided to retire, but returned to make 1946's "A Night in Casablanca" and 1949's "Love Happy". In just 14 films, The Marx Brothers left an indelible mark on cinema and comedy, and AFI voted Groucho, Harpo, and Chico collectively the 20th Greatest Male Screen Legends of All-Time.

Top-billed in “Duck Soup” is Groucho Marx as “Rufus T. Firefly”, Freedonia's new leader. Groucho always played a type of self-serving, innuendo-laden, sarcastic trickster who thrived on irreverence, all of which is in full force as “Firefly”. His rapid-fire wit, biting insults, and blatant disregard for decorum and authority create a gleeful anarchist who mocks the very idea of leadership, often making nonsensical decisions and turning serious situations into absurd farce. It’s brilliant satire. An example of Groucho's comedic gifts can be seen when "Mrs. Teasdale" introduces “Vera", saying "This is 'Vera Marcal' the famous dancer”. "Firefly" replies, "Is that so? Can you do this one?”, demonstrating a zany dance of pseudo ballet with a Broadway kick, then adding, "I danced before Napoleon. No, Napoleon danced before me. In fact he danced two hundred years before me… Here's one I picked up in a dancehall" as he does a playfully goofy bump and grind, followed by "Here's another one I picked up in a dancehall”, pointing to "Mrs. Teasdale”. It’s fast, zany, and fun.

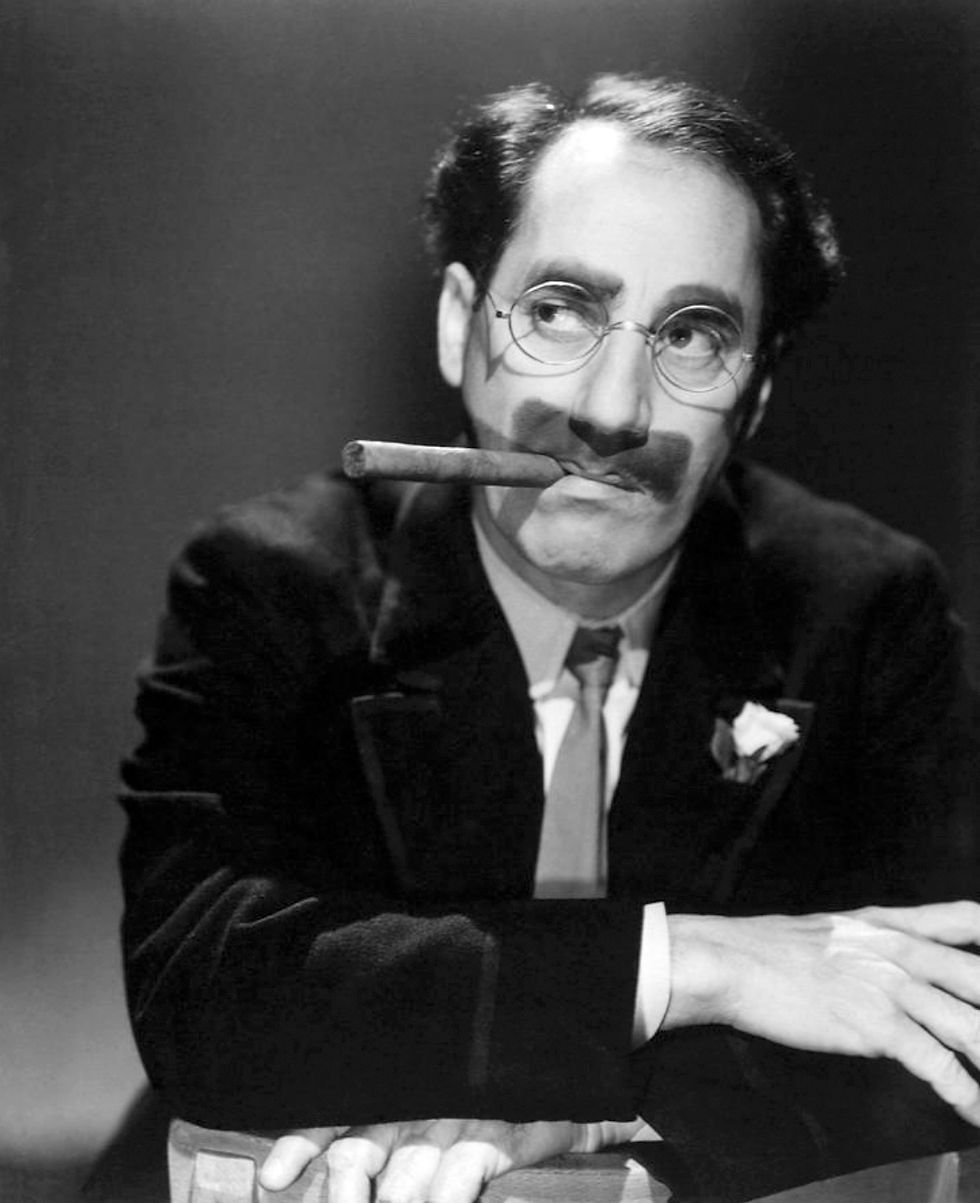

One of America's greatest comedians, Groucho’s humor, greasepaint mustache, exaggerated eyebrows, cigar, and stooped walk made him a comedy icon. He appeared in about a half-dozen films without his brothers, including "Copacabana", and "Will Success Spoil Rock Hunter?" (already on this blog, where you can read a tiny bit more about him), and about a half-dozen TV shows including, most famously, as the ad-libbing host of the radio quiz show "You Bet Your Life” from 1947 to 1960. It was so successful it became an enormously popular TV show from 1950 to 1961. In 1951, he won a Most Outstanding Personality Emmy Award, and in 1974, an honorary Oscar on behalf of the Marx Brothers in recognition of their brilliant creativity and unequalled achievements in the art of motion picture comedy. Married and divorced three times, he had three children, including writer producer Arthur Marx. He was the third oldest of the five Marx Brothers. Groucho Marx died in 1977 at the age of 86.

Second billed in “Duck Soup” is Harpo Marx who plays “Pinky”, a two-bit spy for Sylvania who wreaks havoc wherever he goes. Unlike Groucho’s verbal humor, Harpo's comedy was visual, always as a chaos-creating mute with the innocence of a child and the mischievousness of a devil. Donning a trench coat and curly blond wig (said to actually have been pink and later reddish), one of his signature gags was pulling unexpected items out of his bottomless pockets, and in “Duck Soup” he removes a mousetrap, record album, and a blowtorch among other oddities. He also carries a mean scissors and cuts things at random (cigars, clothes, hair...), and can’t resist the ladies, often chasing them (as he’s about to do with “Trentino’s” secretary). Though Harpo spoke onstage early on, as he developed his character, it became mute. Thus Harpo never spoke in any of his films, communicating through horns, whistles, gestures, exaggerated facial expressions, and in ‘Duck Soup”, tattoos. A silent clown, he adds more emotion to the film than anyone else.

The second oldest of the five Marx Brothers, Harpo dropped out of school in second grade after two classmates threw him out of a second story window (allegedly for being Jewish). His mother pushed him into Groucho and Gummo's singing group, which began his show business career. In his twenties, his mother gave him a harp and told him to learn it, which he did rather seriously, and playing the harp became the true love of his life (earning him the stage name Harpo). In nearly all the Marx Brothers films (not "Duck Soup"), he has a harp solo. Harpo appeared in just a few films sans his brothers, including the 1925 silent film "Too Many Kisses", as himself in 1943's "Stage Door Canteen", and in 1957’s "The Story of Mankind". He also appeared in a dozen TV shows between 1952 and 1962, most famously the aforementioned "I Love Lucy” episode. In the 1950's, he recorded three record albums, "Harp by Harpo", "Harpo", and "Harpo at Work!", and also played harp on Mahalia Jackson's 1964 song "Guardian Angels". He was married once and had four children, including composer Bill Marx. Harpo Marx died in 1964 at the age of 75.

Third-billed in “Duck Soup” is Chico Marx as “Chicolini”, the fast-talking spy. Much of the magic of the Marx Brothers comes from how gloriously their personalities complement one another, and alongside the intellectual suit and tie-clad Groucho and the uncontrollable silent Harpo is Chico’s charming, dimwitted, yet crafty con artist who wears shabby clothes, misunderstands words, and speaks with a fake Italian accent. Always trying to get ahead, he uses his dopiness to manipulate others (frequently with Harpo as his partner and Groucho as his target). As “Firefly” says: “‘Chicolini’ may talk like an idiot and look like an idiot, but don’t let that fool you. He really is an idiot” – and no one plays an idiot more wonderfully fun than Chico. He can say nothing with a lot of words, as when explaining to the lemonade vendor that “Pinky” doesn’t speak: "You no understand. Look, he's a spy and I'm a spy. He worka for me. I want him to find out something but he no find out what I want to find out. Now, how am I gonna find out what I want to find out if he don't find out what I gotta find out?”.

The oldest of the five Marx Brothers, Chico was known to be charming, cunning, and had an insatiable appetite for gambling and women (he’d chase the chicks, earning him the name Chico - pronounced chick-o) – both of which had a hold over him his entire life. At a very young age, he earned money playing piano for silent films, in a brothel, and in vaudeville before joining his brothers onstage. He became a well-respected pianist, and has piano solos in most Marx Brothers’ films (not “Duck Soup”), and later formed his own band, The Chico Marx Orchestra. When Minnie stopped managing her sons, Chico took over, and it’s said he was the reason for the brothers’ financial success. After the Marx Brothers decided to retire at the end of their MGM contract, Chico convinced them to return to the screen for "A Night in Casablanca" and "Love Happy” because he needed money to pay off gambling debts. His gambling issues caused his brothers to eventually take away financial control from him and put him on an allowance for the rest of his life. When a reporter asked how much money he lost gambling in his lifetime, he famously replied, “Find out how much Harpo has, that's how much I’ve lost”. Though a notorious womanizer, he was married twice and had a daughter, Maxine, who published the book "Growing up with Chico" in 1980. Chico Marx died in 1961 at the age of 74.

The fourth and final star of “Duck Soup” is Zeppo Marx as “Lt. Bob Roland”, “Firefly’s" secretary. Groucho famously said, “There has never been a good comedian that didn't have a good straight man”, and Zeppo was one of their best. He doesn’t seem to have much to do in “Duck Soup”, but adds a lot with a little, as in his scene explaining his plan to get "Trentino” out of the way, telling "Firefly”, "Now you say something to make him mad and he'll strike you. Then we force him to leave the country”. Zeppo’s funny at taking jabs (and a slap) from Groucho, letting us see his knack for comedy. He's also the first person to sing in the film, and is seen alongside his brothers in the film’s very amusing and elaborate production number "This Country's Going to War" singing, dancing, using guards as xylophones, and playing banjos in a mash-up of parodied popular songs, including the spiritual "All God's Chillun Got Wings” (changed to "All God's Chillun Got Guns”). He beautifully sets up “Firefly” for comedy in the battle scene, telling him “You’re shooting your own men”. While his brothers are all assertive (to say the least), Zeppo watches and reacts to them with a seriousness (and faint wink) that heightens their comedy. He had a sleek finesse all his own.

With no desire to perform, Minnie pushed Zeppo into his brothers' act to replace Gummo. Zeppo knew their act well and would take over for any of them when they were too ill to perform, and did so expertly. Offscreen, he was apparently the funniest brother. While his brothers were forming their own comedic personas, Zeppo played their straight man as well as romantic leads when needed. He appeared in one film without his brothers, 1925’s "A Kiss in the Dark”, and costarred in all five Marx Brothers films at Paramount from "The Cocoanuts" to "Duck Soup". Unhappy with his thankless roles and eager to stop performing, he retired from acting after "Duck Soup", and many feel the Marx Brothers were never as good or funny as they were with him. Zeppo then worked with Gummo as a theatrical agent (representing his brothers, Barbara Stanwyck, Fred MacMurray, Lana Turner, and others). He was also as an engineer, horse breeder, businessman, and inventor, and his inventions include the Marina Clamp (which safely secured atom bombs inside B-29’s), and the first wrist-worn heart monitor. He was also a gambler and apparently had friendships with mobsters and organized crime figures. He was married twice, including to model Barbara Blakeley (who left him for Frank Sinatra). Zeppo Marx died in 1979 at the age of 78.

A large reason “Duck Soup” arguably stands as the Marx Brothers’ best film is because it was directed by one of Hollywood’s top directors, Leo McCarey. McCarey knew how to allow the unrestrained Marx Brothers to thrive within a structured comedic framework and keep their comedy seemingly spontaneous, adding a layer of satirical depth to a presumably nonsensical plot. He keeps us focused in the middle of all the chaos and astoundingly quick non-stop humor. Not an easy task.

McCarey’s unobtrusive camera work, intelligent framing and editing are key in showcasing the comedy. You’ll notice very little camera movement with strategic edits of close, medium, and long shots to emphasize comedy and visual gags. Whether in the lemonade vendor scene or at the chamber of deputies meeting, McCarey knows exactly how to present humor to maximize laughs and keep us interested.

A man who loved using improv, McCarey was known to pause filming and play piano until a new, better idea struck him. He had major input in shaping “Duck Soup”, such as bringing comedian Edgar Kennedy onboard to do his brand of comedy as the lemonade vendor, and adding the famous mirror scene to the film (having directed a similar gag with a window shade in the 1926 Charlie Chase comedy “Mum's the Word”). His conceptual and technical contributions, gift at balancing chaos with coherence, and ability to allow the Marx Brothers’ humor to dominate is why “Duck Soup” remains a treasure.

Originally a lawyer, Los Angeles-born Leo McCarey had trouble getting clients and decided to try his hand at movies. A friend referred him to Hollywood writer, director, and editor Tod Browning, who hired McCarey as his apprentice and script girl (now called script supervisor). McCarey was quickly promoted to director, as he told Peter Bogdanovich in the book "Who the Devil Made It": "Because of my legal education I had developed quite a vocabulary, and the heads of the studios in those days didn't have the advantage of advanced education. And they thought I was brilliant because I used big words. So they made a director out of me at the end of one picture!“. That film was 1921's "Society Secrets” and with his great sense of humor, McCarey was soon working for comedy king Hal Roach as a gag writer for Our Gang comedy shorts, then directing actor Charley Chase in a slew of highly successful silent comedies like 1926's "Mighty Like a Moose" and "Crazy Like a Fox”. They were character driven and farcical rather than the typical slapstick of the day, and made Chase a giant comedy star. McCarey also paired Stan Laurel with Oliver Hardy and helped develop their comedy style, making it slower, more natural, and more subtle than the frenetic comedy at the time. He oversaw many of the legendary duo's films, wrote many of their screenplays, and directed a handful as well.

When the Marx Brothers saw McCarey’s 1932 musical comedy “The Kid from Spain”, they immediately requested he direct their next film at Paramount, but McCarey didn't want to work with them and refused. That's when the brothers briefly walked out of the studio, so with them gone, McCarey renewed his deal at Paramount. Once the brothers settled with and returned to Paramount, he was forced to direct "Duck Soup". As he told Bogdanovich, "The amazing thing about that movie was that I succeeded in not going crazy. [The Marx Brothers] were completely mad. I enjoyed shooting several scenes in the picture, though. My experience in silent film influenced me very much, and so usually I preferred Harpo. But it wasn't the ideal movie for me. In fact it's the only time in my career that I based the humor on dialog, because with Groucho it was the only humor you could get. Four or five writers furnished him with gags and lines. I did none of them”.

McCarey directed more comedy giants like W.C. Fields, George Burns, Gracie Allen, Harold Llyod, and Mae West, before making more socially conscious, sentimental, and sometimes religious films like "Ruggles of Red Gap", "Make Way for Tomorrow", "Love Affair", and the screwball comedy "The Awful Truth”, which won McCarey a Best Director Academy Award and turned Cary Grant into a star (many say Grant's screen persona emulated the tall, good looking, and funny McCarey). One of the most famous and successful Hollywood film directors of the late 1930s and early 1940s, McCary earned a total of eight Oscar nominations, winning three (the others for Best Screenplay and Best Director for 1944's "Going My Way”). McCarey’s other films include "The Bells of St. Mary’s", "My Son John”, "Belle of the Nineties”, and his final, 1962's "Satan Never Sleeps”. He was married once for over fifty years until his death. Leo McCarey died in 1969 at the age of 72.

No mention of “Duck Soup” would be complete without talking about the person Groucho called “practically the fifth Marx Brother”, and that’s Margaret Dumont who plays strait-laced, dignified, rich widow “Mrs. Gloria Teasdale”. The highly respectable “Mrs. Teasdale” represents the establishment and is the target of many of “Firefly's” insults, quips, and flirtations, and Dumont is outstanding as Groucho’s foil. No matter how crazy or crude he gets, she's always innocent and earnest, taking whatever he says to heart. In her eyes he can do no wrong, and her reactions make his jokes even funnier.

A fabulous example of Groucho and Dumont's comedic back-and-forth give-and-take happens at his welcoming reception:

“Firefly”: ”Not that I care, but where is your husband?"

“Mrs. Teasdale” (forlorn): ”Why… he's dead.”

“Firefly”: "I bet he's just using that as an excuse.”

“Mrs. Teasdale” (proudly): ”I was with him to the very end.”

“Firefly”: "No wonder he passed away.”

“Mrs. Teasdale” (highly dramatic): ”I held him in my arms and kissed him.”

“Firefly”: "Oh I see, then it was murder. Will you marry me? Did he leave you any money? Answer the second question first”.

“Mrs. Teasdale” (matter of factly): "He left me his entire fortune.”

“Firefly”: "Is that so? Can't you see what I'm trying to tell you? I love you!"

“Mrs. Teasdale” (happily flattered): "Ohhh, your Excellency.”

“Firefly”: "You're not so bad yourself.”

Because Dumont was so convincing playing it straight, many thought she didn’t understand Groucho’s jokes or insults (a rumor she and Groucho perpetuated). But Dumont did, and those rumors certify her masterful, precise comedic talent, timing, and chops at making something funny and real. She’s the glue grounding all the zaniness to some sort of reality.

A trained opera singer and actress, by her teens Brooklyn-born Margaret Dumont performed on stage, and briefly retired to marry a millionaire in 1910, but made her film debut as an aristocrat in the 1917 silent film "A Tale of Two Cities". After her husband's death in 1918, she returned to the stage, mostly in musical comedies, making her Broadway debut in 1921's "The Fan". More stage work followed, including as a stuffy wealthy widow on Broadway with the Marx Brothers in "The Cocoanuts" and again in "Animal Crackers". When the Marx Brothers were given contracts at Paramount to make screen versions of those shows, so was Dumont. To everyone's joy, she returned with the Marx Brothers in "Duck Soup". Dumont appeared in four more Marx Brothers films ("A Night at the Opera", "A Day at the Races", "At the Circus", "The Big Store"), and has become immortal from her work with them. She appeared in over a half dozen TV shows and 50 other movies (often uncredited) including "Never Give a Sucker an Even Break", "Tales of Manhattan", "High Flyers", "Anything Goes", "Auntie Mame", and her final, 1964's "What a Way to Go!". Once widowed, she never remarried. Margaret Dumont died in 1965 at the age of 82.

This week’s classic is unbridled comedy at its best, with political undertones that sadly remain relevant. It’s also a glorious introduction to one of comedy’s most important and influential teams. Enjoy the highly original and very funny “Duck Soup”!

This blog is a weekly series (currently biweekly) on all types of classic films from the silent era through the 1970s. It is designed to entertain and inform through watching a recommended classic film a week. The intent is that a love and deepened knowledge of cinema will evolve, along with a familiarity of important stars, directors, writers, the studio system, and more. I highly recommend visiting (or revisiting) the HOME page, which explains it all and provides a place where you can subscribe and get email notifications of every new post. Visit THE MOVIES page to see a list of all films currently on this site. Please leave comments, share this blog with family, friends, and on social media, and subscribe so you don’t miss a post. Thanks so much for reading!

YOU CAN STREAM OR BUY THE FILM ON AMAZON

OTHER PLACES YOU CAN BUY THE FILM:

As an Amazon Associate I earn from qualifying purchases, and any and all money will go towards the fees for this blog. Thanks!!

TO READ AFTER VIEWING (contains spoilers):

In case you're wondering, the N.R.A. logo at the beginning refers to the National Industrial Recovery Act of 1933, a program that was part of President Franklin D. Roosevelt’s New Deal to help the US recover from the Great Depression.

“Duck Soup” contains countless contemporary references (most are probably lost on us today), and I’ll mention one that’s a bit jarring. It’s when “Firefly” talks about war with “Mrs. Teasdale”, “Vera”, and “Trentino”, and tells them: “My father was a little headstrong. My mother was a little armstrong. The Headstrongs married the Armstrongs and that’s why darkies were born”. The offensive line seems to come out of nowhere, but it was referencing a popular song of the day, "That's Why Darkies Were Born", recorded by both Paul Robeson and Kate Smith. Many felt the song was racist, though some saw it as satirizing racism. I think it's used in this film simply because it was popular at the time.

Fun, unusual and full of different elements!! It is very unexpected movie! I like the contrast of the different comedy styles that each of the brothers and also the main character have! It is definitely crazy at times, it makes its political criticism very well! The mirror scene I found it fantastic! Thank you Jay for teaching us so much!